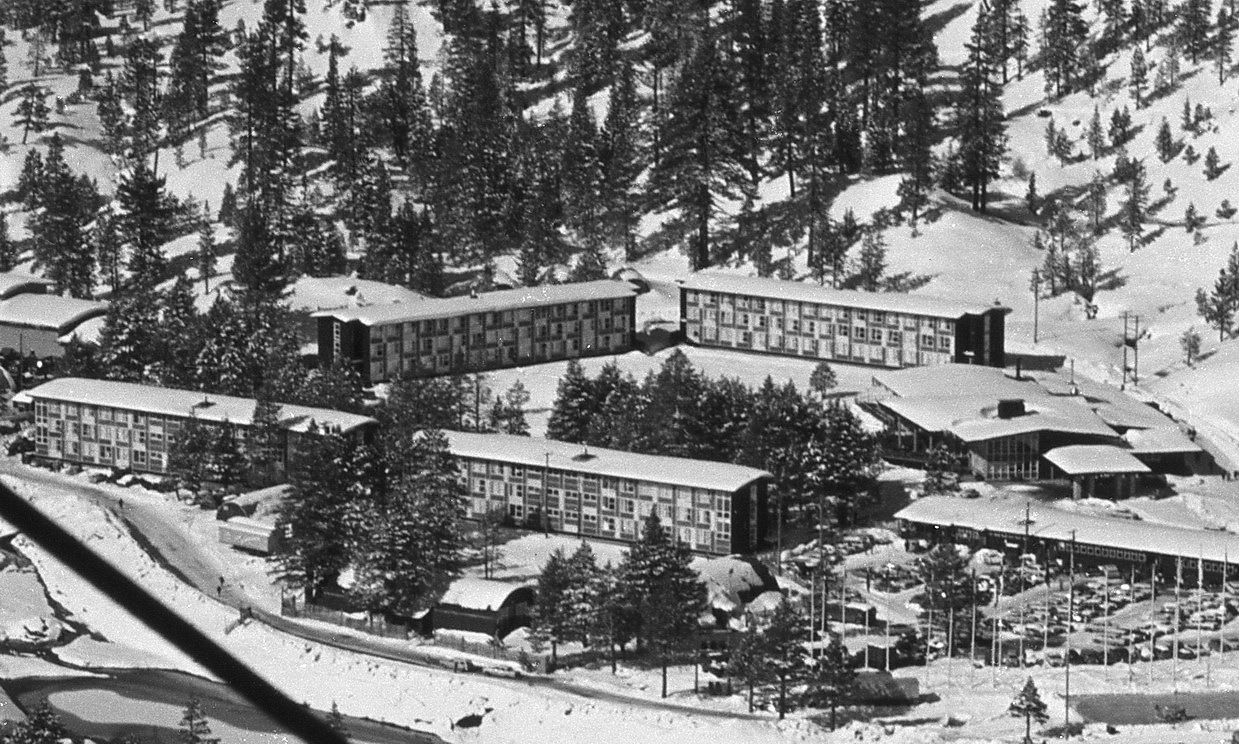

01 – Aerial view of Olympic Village and athlete center. Photo by Bill Briner.

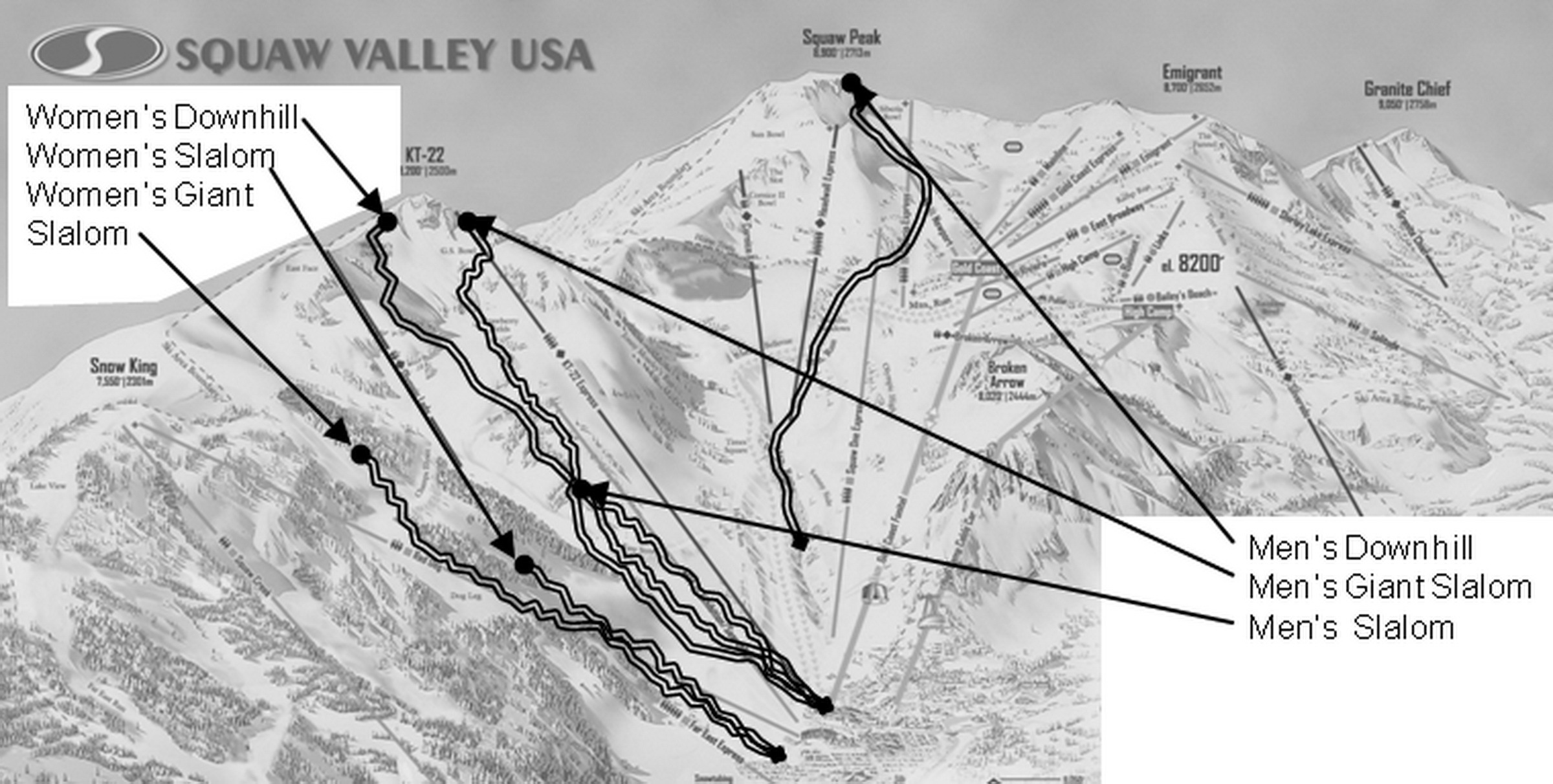

02 – Alpine race courses shown on current ski area map, courtesy of Squaw Valley USA.

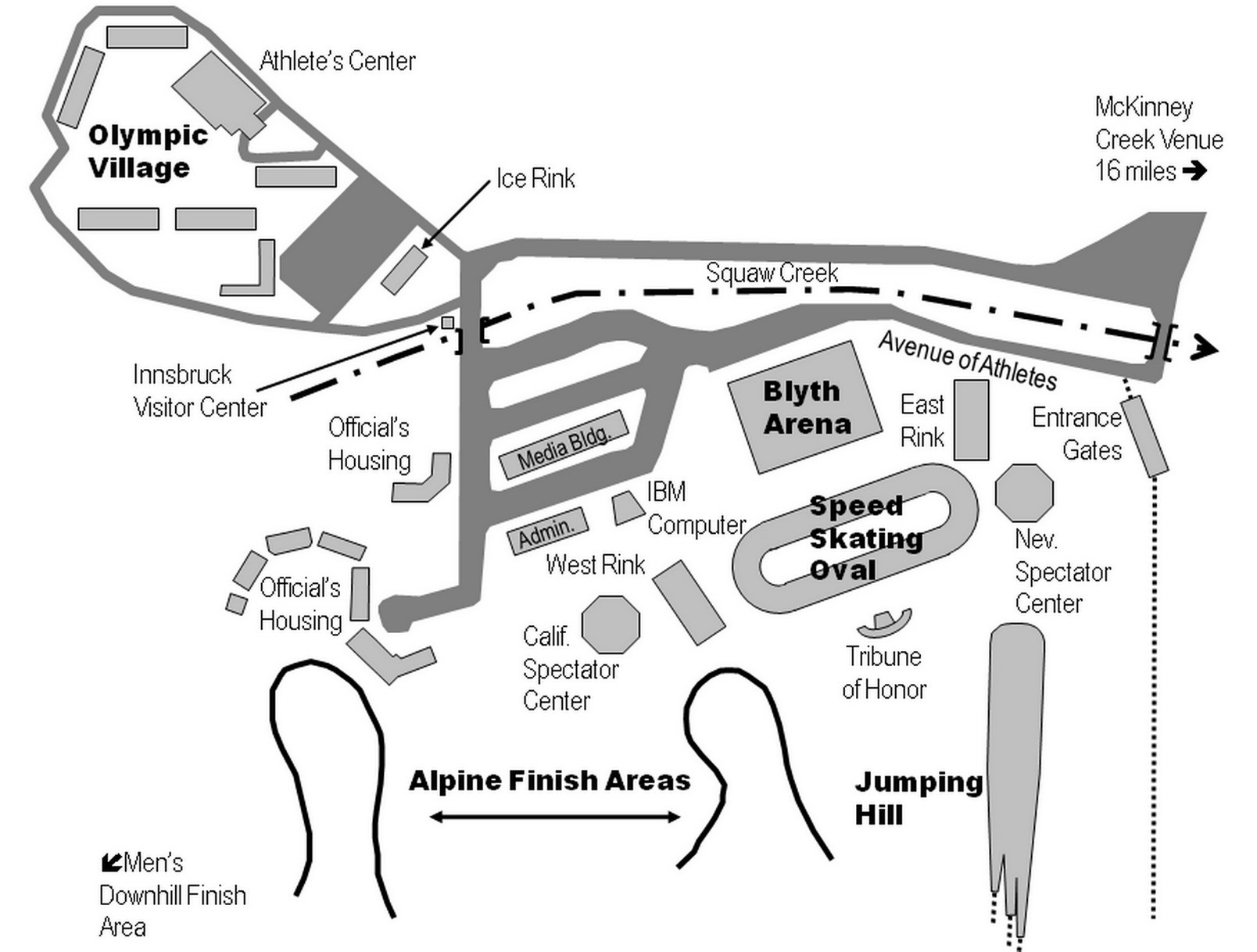

03 – View of the jumping hill from the landing area and run out. Photo by Bill Briner.

Adding to the daunting task of building Olympic Village, the rumblings of controversy over the location of the Olympic Winter Games had not subsided with the winning of the bid, and some Europeans continued to feel slighted.

There was nothing to do but get to work building an Olympic Village that would prove the naysayers wrong. Two organizations were tasked with the role: The VIII Olympic Winter Games Organization Committee, an entity directly controlled by the International Olympic Committee, was responsible for planning and staging the Winter Games, and the California Olympic Commission was to expend public funds and private donations to acquire land and construct the facilities to host the Winter Games.

Among its first actions, the Commission ordered the preparation of a planning and project report. Cushing’s initial proposal for an economical and modest Olympics quickly receded as costs escalated and organizers estimated a total of $5 million to realize Cushing’s concept of housing the athletes and officials in an Olympic Village in Squaw Valley. Of course, the tens of thousands of spectators expected to attend the events would also need to be accommodated. In the end, the Olympic facilities totaled $15 million, paid largely by the State of California, Federal Government, State of Nevada, and corporate donors.

One of the advantages of lacking almost all of the facilities and infrastructure needed to stage the games was that the planners had the unprecedented opportunity to conceive a winter sports park and athletes’ village in close proximity to each other. In past Winter Games, the organizing committees housed athletes in hotels and dormitories spread throughout the region among dispersed competition venues. This exceptional opportunity to mix rivals was particularly significant, considering the prevailing Cold War tensions and post-World War II animosities.

That unprecedented opportunity culminated in a self-contained village with all amenities fitting for athletes and support staff, including a recreation center and physical therapy rooms, with international foods prepared on site and served all day. Access to the village was tightly controlled to keep out media and fans, and the consensus among athletes was that the arrangement was conducive to greater social interaction among nations.

The transformation of Squaw Valley did not stop there. In addition to the first Olympic Village of its kind, organizers designed and built a world-class winter sports park to accommodate each of the major competitions, including the alpine courses, men’s and women’s slalom and giant slalom courses, men’s and women’s downhill courses, the ski jumping hill, and the McKinney Creek cross-country and modern winter biathlon venue, located 16 miles south of Olympic Village on the west shore of Lake Tahoe.

In the midst of it all stood Blyth Memorial Arena, the iconic centerpiece for the Winter Games, which served as the setting for the opening and closing ceremonies and the venue for the hockey and figure skating events. In a feat of engineering, the bleacher sections on one side could swing out to open the entire arena to viewing of the speed skating oval and awards stage during the opening and closing ceremonies.

The awards stage, designed by Walt Disney himself, was comprised of the Tribune of Honor, a raised platform with the Olympic flame burning at its center, backed by the 80-foot tall Tower of Nations. Two immense statues of a man and a woman flanked both sides of the platform. The Tower of Nations displayed the crests of all participating nations.

Also developed by Disney was the majestic Avenue of Athletes, thirty larger-than-life wire mesh, papier-mâché and stucco sculptures of athletes that greeted spectators as they entered the Olympic competition area. The statues depicted athletes engaged in Winter Games events, such as hockey, alpine skiing, figure skating, ski jumping, and biathlon.

In addition to the various competition venues and athlete housing, additional buildings were constructed in the valley to serve the needs of spectators and carry out such a massive and complex event, including the California and Nevada Olympic Centers to house spectator amenities, administrative and support buildings, extensive medical facilities, and the Squaw Valley Chapel.

It’s no wonder that the international world doubted Alexander Cushing and his team would be able to create all of this from a raw, unimproved valley (what had been referred to as a virtual “picnic area”). But with a unique vision reinforced by influential friends and luminaries, and a whole lot of work, that’s exactly what he did.